Early computer game history often gets overlooked.

I’m just as guilty as anyone of overlooking computer game history. So for this series, I made a conscious effort to broaden my investigation. I was going to get to the bottom of the first computer game box art, even if it predated game boxes.

Along the way I found a few kernels of computer game history so far off the beaten path that they’ve never been written about before. But before we get into that, I should explain the concept of type-in games for those of you who are unfamiliar.

What Are Type-In Games?

Have you ever had to redeem a game by typing in a random string of numbers and letters? While that can be a pain, imagine if instead you had to type in multiple pages of code before you could run your game.

That’s exactly what computer gamers did in the ‘70s and early ‘80s. Before discs or disks or cartridges or cassettes there were games on paper. A number of computer magazines included free games in the form of typable program listings, essentially the low-tech equivalent of including a demo disc or sampler.

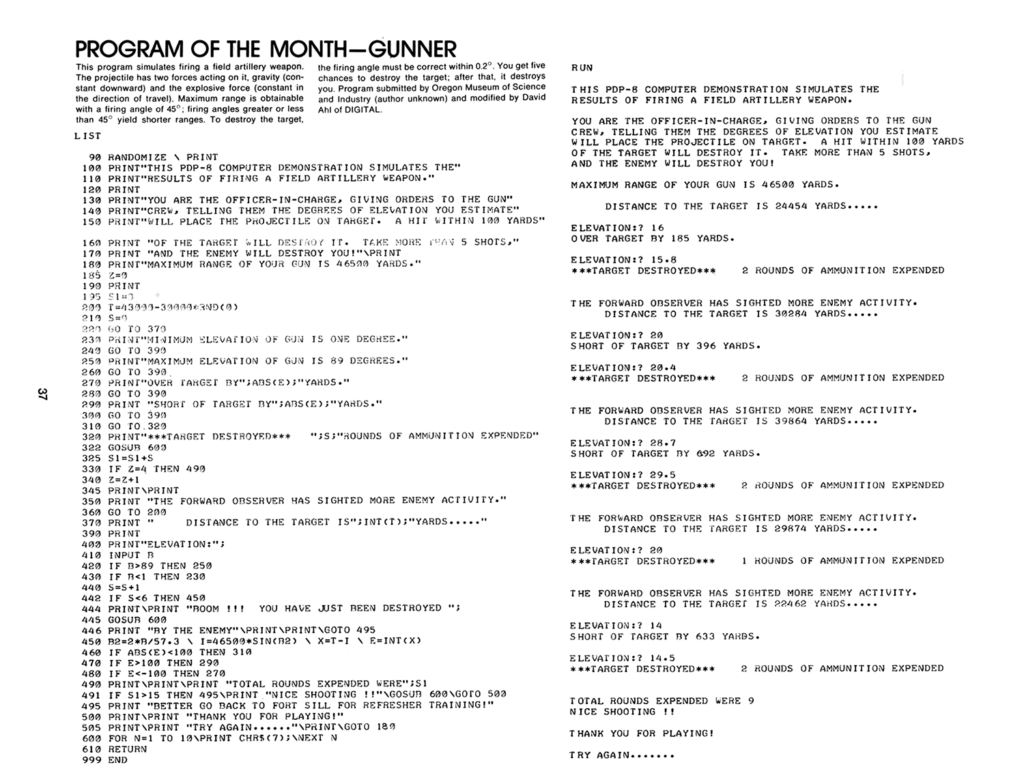

I’m not sure exactly who started it, but I think it’s safe to say it was popularized by David H. Ahl in the pages of Creative Computing.

Ahl might even be the one who started it; before Creative Computing, he’d been printing games in EDU, a newsletter for schools published by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). EDU was filled with ideas for fun things teachers could do with the computers their schools bought from DEC.

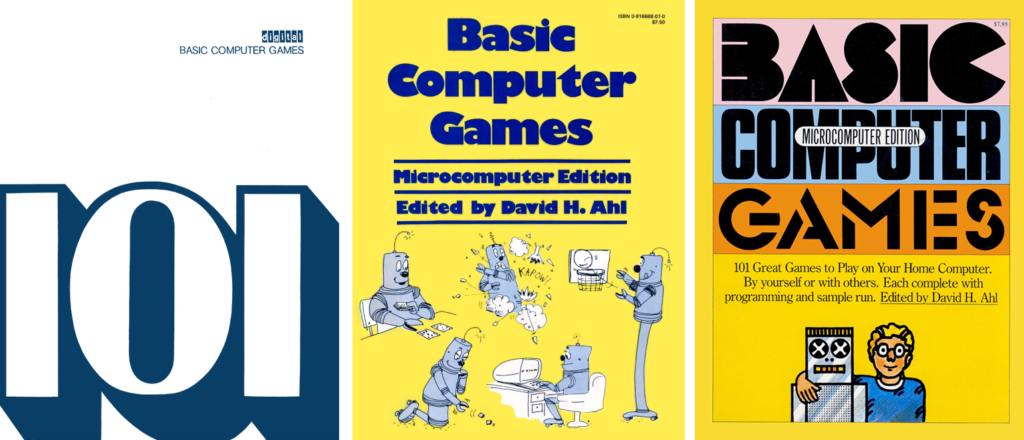

In 1973, EDU issued an open call for readers to submit games for inclusion in what would be the low-tech equivalent of a game compilation, i.e. a book. But contrary to popular belief, David H. Ahl’s 101 BASIC Computer Games wasn’t the first collection of type-in games.

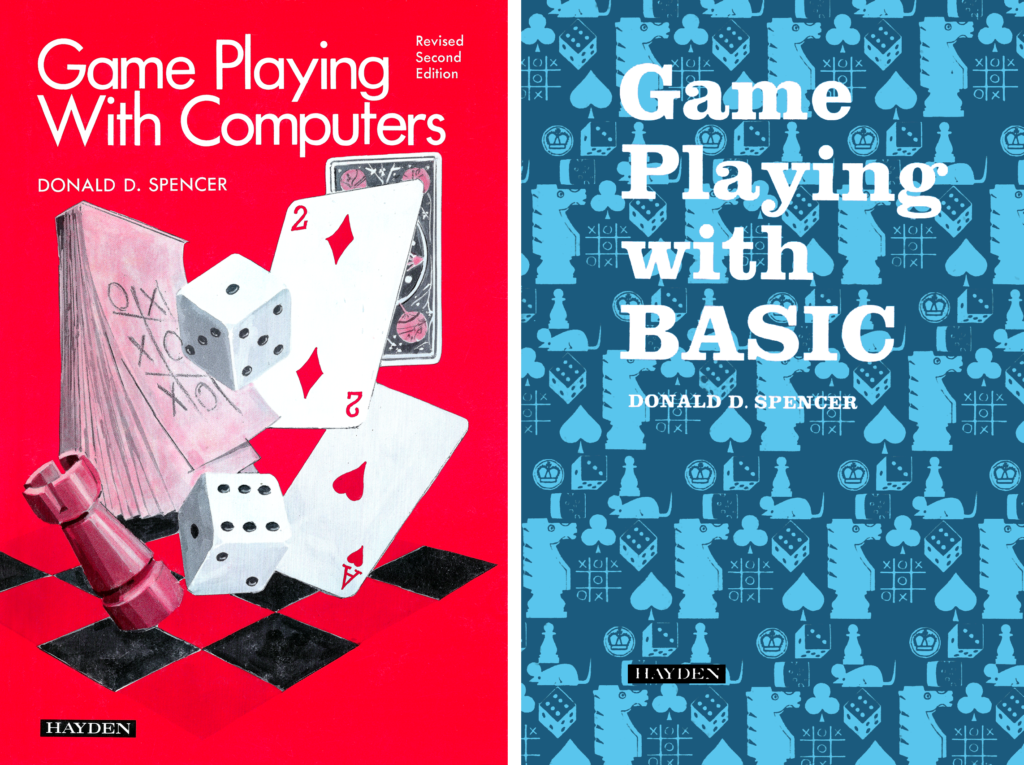

Game Playing With Computers was released five years earlier.

Now, some might question whether type-in games actually count as a commercial video game release. I raised a similar question last month regarding Odyssey games. But if they do count, Game Playing With Computers could be considered the first professionally-packaged computer game compilation. It’s not the first cover art for a stand-alone computer game, but it’s technically the first computer game cover art.

And what a cover it is. Sure, it’s printed horribly off-center. And the typography isn’t very inspired. But there’s just something I love that weird illustration. I mean, why is it covered in Pong paddles? Was it predicting the ball-and-paddle craze?

Ah, but those aren’t paddles at all; they’re hole punches. The illustration is designed around a punch card, which was a readable storage medium for computers before magnetic tape. The book didn’t come with a punch card, but I guess it was being used as visual shorthand for “computer program” the same way a floppy disc is used as visual shorthand for “save file” today.

The game pieces included in the design represent the admittedly very small variety of games in the book: mainly simulations of board games, casino games, and a lot of pre-Sudoku number games and puzzles.

Which is probably why it isn’t as fondly remembered as 101 BASIC Computer Games.

David H. Ahl’s book had several things going for it over Spencer’s:

- It had more games. Game Playing spent so many pages on theory, game rules, history, and how to program that there wasn’t much room for actual game listings, whereas 101 BASIC just hits you with a hundred games.

- It had better games. Game Playing merely simulated popular old standards, nothing that was original or unique to computers, while 101 BASIC featured games like “Hamurabi” and “Rocket” (aka “Lunar”).

- It was in BASIC. BASIC was a simple programming language that was quicker and easier for kids to pick up and understand. Game Playing focused mostly on FORTRAN, with only a small BASIC section at the end.

Which of the two books had the best cover depends on your preferred brand of weirdness: are you more into collage-of-shapes weird, or Schoolhouse Rock weird?

But the latter isn’t the only cover you’re likely to find.

Ahl’s book was printed in several editions with a number of different covers, and two different titles: DEC published 101 BASIC Computer Games, and later Creative Computing published Basic Computer Games.

My personal favorite cover is DEC’s Third Edition with the giant “101,” but maybe that’s just my love of typography.

Ahl left DEC not long after convincing them to publish the book. He was disappointed by their lack of interest in pursuing a new direction: single-user computers.

You see, at the time DEC’s bread and butter was “minicomputers,” large refrigerator-sized cabinets that were only “mini” compared to mainframe computers. Minicomputers were typically time-shared by multiple users on working separate keyboard terminals.

The idea of a stand-alone single-user computer baffled the head of DEC. Why would anyone need an entire computer all to themselves?

Fortunately, Ahl left on good enough terms with DEC that they allowed him to co-distribute and eventually publish his own editions of 101 BASIC Computer Games (later renamed Basic Computer Games), just in time for the arrival of the “microcomputer.”

And the arrival of a wave of type-in game book collections.

A New Micro-Genre

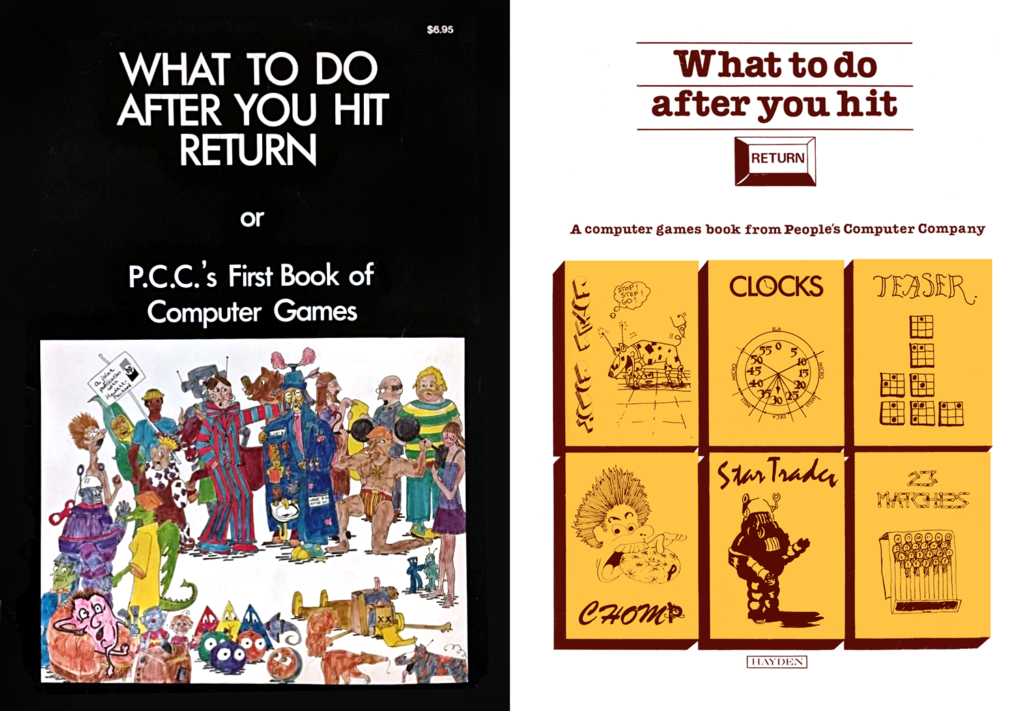

What To Do After You Hit Return is probably the most notable of the collections that followed 101 BASIC Computer Games, and just like that book it started with a newsletter.

People’s Computer Company started in 1972, just a few years after EDU and a few years before Creative Computing. And like those magazines, PPC included type-in games, such as the influential proto-adventure “Hunt The Wumpus.”

The newsletter was located in the San Francisco Bay Area, which is probably why the art direction had a more counterculture vibe. Unfortunately, counterculture art had shifted from psychedelic Art Nouveau to subversive refrigerator art.

Hit Return was given a new cover in 1980 when it was reprinted by the mysterious Hayden Books. I say “mysterious” because they spent the ‘70s buying up seemingly every computer book that wasn’t Basic Computer Games, yet the internet knows almost nothing about them.

They even reprinted Game Playing With Computers, again with a new cover. This one is more literal, but less fun and weird. Maybe they were saving the better cover for Game Playing With BASIC, a smaller paperback edition revised to focus on BASIC games.

But before I get into who the hell is Hayden Books, I want to address an even more pressing question: Who the hell is Donald D. Spencer?

If I told you Spencer had a Ph.D, you might assume he was some stuffy professor who wrote a book about computer games as a one-off thing. I bet you’d never imagine that this maniac wrote over 100 computer-themed books from 1968-1999, written for a variety of age groups and ranging in subject matter from Invitation To Number Theory With PASCAL to Computer Humor. And the computer books make up only half of his total bibliography.

He’s like the R.L. Stine of computer books, yet almost nothing is written about him.

Here’s what I know:

- I know that he worked at RCA and UNIVAC after getting a degree in mathematics.

- I know that he was a programming analyst at General Electric when he started a side project called Abacus Computer Corporation in 1967.

- I know that he started Camelot Publishing Company in 1975, apparently self-publish books that didn’t get picked up.

But what’s his story? How did he go from programming to writing books? Why did he write so many? How did he write so many? And why did he stop?

We might never know. All I can say is it might be for the best that he retired when he did. While digging, I discovered his final computer book contained a number of careless errors and embarrassing plagiarism. A sad ending for the creator of the first professionally-packaged computer game compilation.

But that brings us to another mystery: who created the first professionally-packaged stand-alone computer game?

Forgotten Innovators

SCELBI wasn’t the first to create a microcomputer, but they were the first to market them for home use.

Nat Wadsworth was so ready for the home computer revolution, he bought a refurbished DEC PDP-8 for just that purpose (see the photo earlier in this article). So when he learned Intel was creating an 8-bit CPU on a chip, called the “8008,” he immediately saw the potential.

Wadworth recruited Robert Findley, a friend he met at the University Of Connecticut, and the two founded SCELBI Computer Consulting. (SCELBI stood for “SCientific ELectronic BIological” but was never written out.)

But computer hobbyist magazines like Creative Computing and BYTE wouldn’t exist for another year, so they started out by advertising their computer to ham radio enthusiasts.

The two supplemented their hardware by writing software, distributed in book form. But in an ironic twist, the books ended up being more profitable than the computers. So at the very end of 1975, SCELBI dropped computers and became a software company. Or a book publisher, depending on how you look at it.

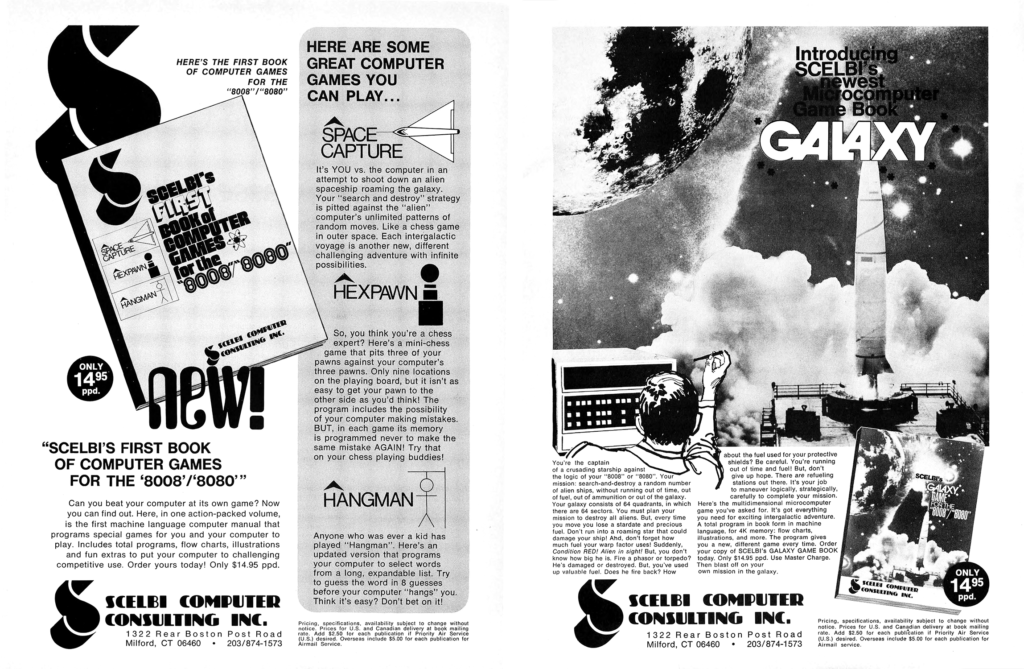

And as was the fashion, they produced a computer game compilation.

I’m conflicted about the cover. I love the fonts in use, but the way all the elements are assembled, it all feels a little bit “off.”

But the book itself also appears a bit “off” at first glance. Three games that fill an entire 100+ page book? What’s going on here?

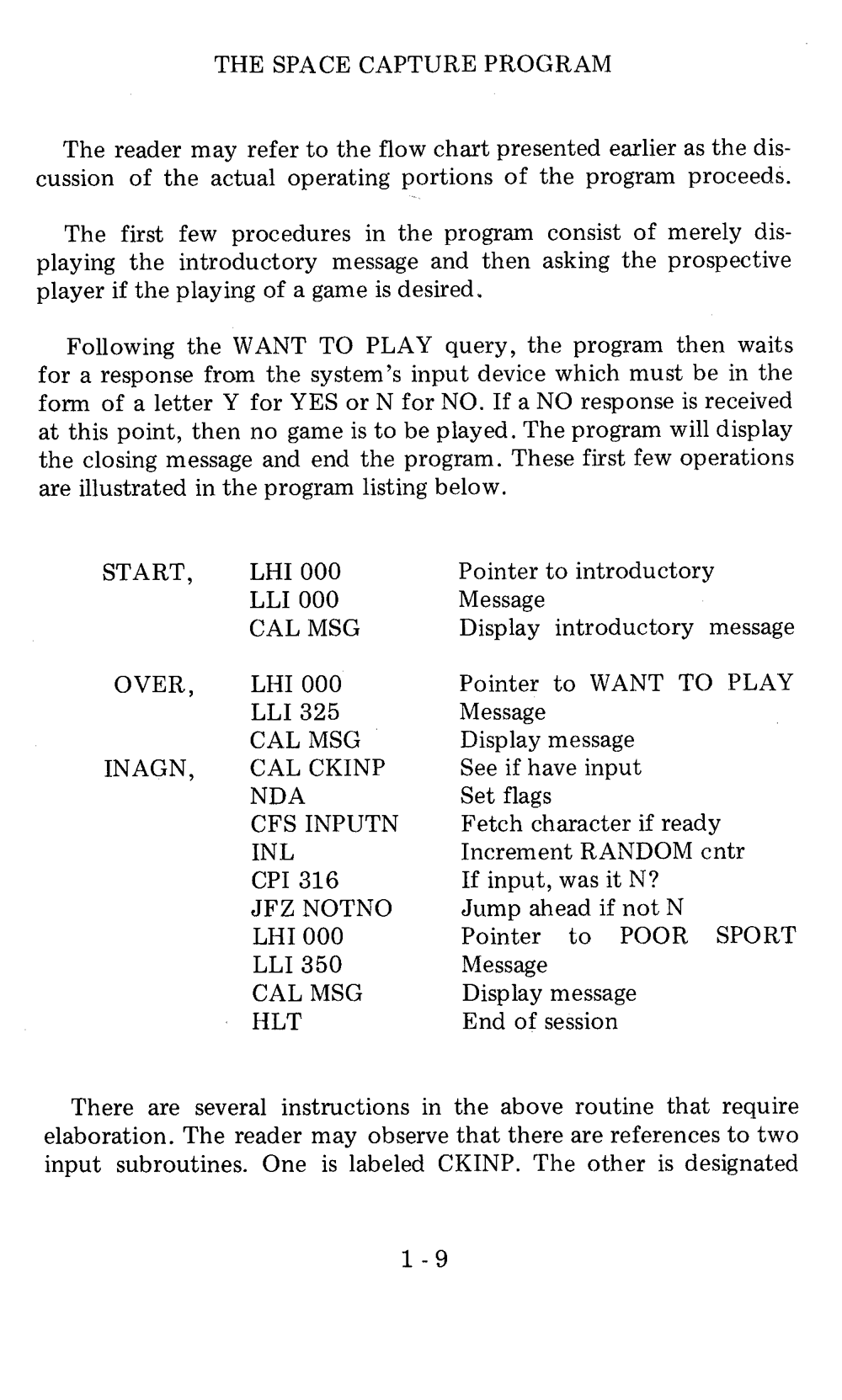

The answer is: some assembly required. By which I mean these games weren’t written in BASIC or FORTRAN, but in assembly language.

Assembly language was more flexible and efficient, but harder to learn. The target audience might’ve been adult hobbyists rather than kids, but Wadworth and Findley still seemed concerned about ease of use. First Book goes out of its way to make the code as easy to comprehend as possible, with extensive notes and explanation.

The notes are so extensive that a programmer friend of mine suggested this might be an early example of “literate programming” a decade before Donald Knuth coined the term.

Literate programming means writing your program out in plain language, quoting the relevant code fragments being described. This is the reverse of how things are usually done, where short notes are later added to the code as almost an afterthought.

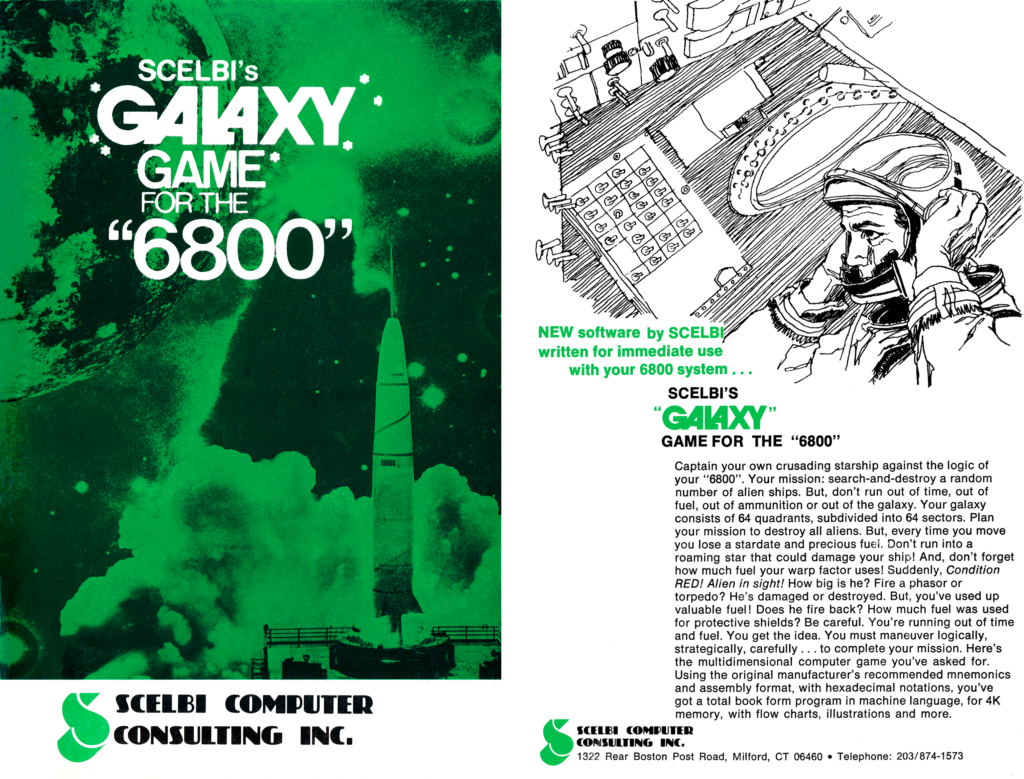

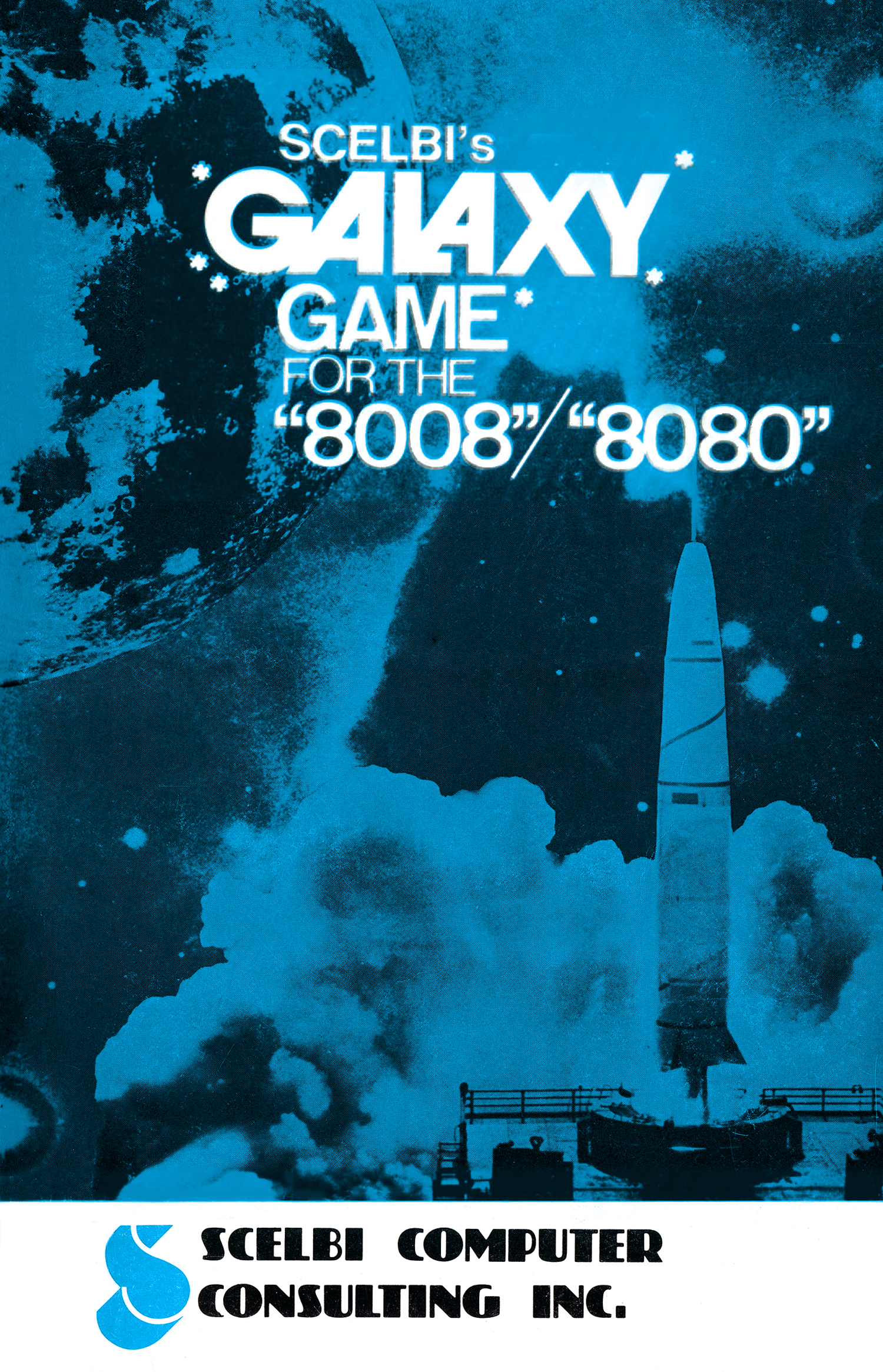

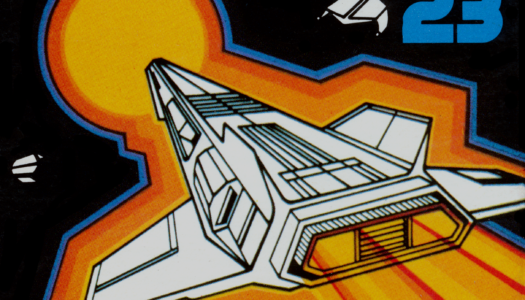

The next game book continued this approach, but differed in two ways: Robert Findley wrote it solo, and the entire book was devoted to a single game: SCELBI’s Galaxy Game For The “8008” / “8080”, or simply Galaxy.

Although SCELBI wasn’t the first to sell a stand-alone game on paper, but they were the first to professionally package it. The stand-alone games offered by other companies were merely packets of Xeroxed pages with a single staple in the corner. But not SCELBI. SCELBI gave Galaxy the full book treatment, complete with real binding and an actual cover.

They even ran a full-page ad for the game in BYTE magazine, giving us a firm indication of when it was first published. An ad for SCELBI’s First Book Of Computer Games ran in the March 1976 issue, and the ad for Galaxy ran in the May 1976 issue.

A copyright listing from late 1976 gives a publication date of April 16, 1976, and gives the book’s full name as “Scelbi’s Galaxy game for the ‘8008/8080,'” but the ad refers to it as “SCELBI’s newest Microcomputer Game Book GALAXY.” Not only is this the first full-page ad for a standalone computer game, it’s also the first time a pre-release mock-up of a game’s box art appeared in an ad.

The final cover design isn’t perfect, but I sort of love its imperfections. In particular, the “LA” in “GALAXY” with the “L” kind of stabbing the “A” is a rare example of one of Avant Garde’s otherwise awesome ligatures that I don’t particularly like, but ultimately I forgive it because the way the cheesy ’70s typography is mixed with cheesy ‘50s B-movie imagery feels so ominous and mysterious; weirdly epic and epicly weird.

The “6800” edition is even better, because green makes it look even more supernatural. Plus, the larger number makes the title look more epic.

And can we take a moment to admire the back cover illustration? It’s probably stock art, but it’s great.

Unfortunately, the game itself isn’t anything special. It’s just another clone of BASIC “Star Trek” — which was already widely available in 101 BASIC Computer Games as “Space War” — but converted to assembly language.

A third edition of Galaxy was published, modified for the “8080,” however this time they went the less expensive Xerox packet route. SCELBI continued to publish computer-related books (complete with professional printing), but this would be their last computer game.

At first I thought Galaxy might be the only stand-alone type-in game with book binding in existence, since cassette tapes arrived soon after, but I did find one more.

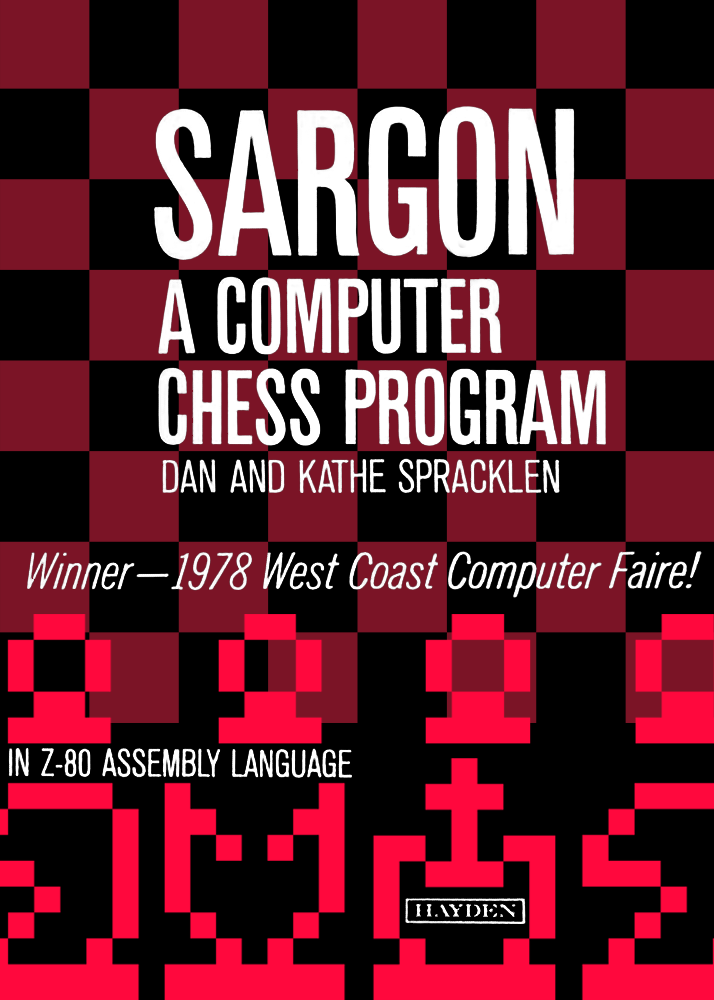

Sargon was created by Dan and Kathe Spracklen, who met through a mutual interest in chess. Chess programs were still such a novel concept that chess tournaments existed where chess programs were pitted against each other. Dan and Kathe entered the 1978 West Coast Computer Fair…and won!

Afterwards, they took out an ad in BYTE magazine to sell Xeroxed packets of the game. But then, they got a book offer from — who else? — but Hayden Books.

Okay, let’s talk about Hayden Books. As I mentioned, the internet has almost nothing on them, and their sparse two-sentence Wikipedia entry isn’t very helpful. Here’s what I found:

Hayden Publishing Company was founded in 1952 by T. Richard Gascoigne and James S. Mulholland, II, as a publisher of electronics magazines like Electronic Design and Microwaves. Hayden Books was established in 1961, when they acquired two textbook publishers.

Gascoigne was removed from the company in 1966 over a dispute about how he was running things. Under Mulholland’s direction, Hayden gradually became more computer focused.

Hayden Publishing launched Computer Decisions magazine in 1969, and acquired Personal Computing in 1980. In the years between, the book division published an increasing number of computer books.

Hayden Software was established in 1979 to publish software on tape. I’ll talk more about games on tape in a future article. Hayden’s first were, naturally, Game Playing With BASIC and Sargon.

And then, in 1982, Hayden bought SCELBI.

But Hayden weren’t planning to release tape versions of First Book or Galaxy. No, Hayden seemed much more interested in SCELBI’s popular “Cookbook” series.

SCELBI wasn’t the first to publish a cookbook not about food, but they were the first to do a cookbook about programming.

Today, programming cookbooks are an enduring subgenre. Multiple publishers sell cookbooks devoted to languages like Python, C++, SQL, and platforms like Unity, Unreal, and iOS. But it all started with SCELBI’s Gourmet Guide & Cookbook for 8080, 6800, 6502, Z80, and the Graphics Cookbook For The Apple.

Admittedly, the concept was clearly borrowed from Don Lancaster’s popular circuit design books, RTL Cookbook and TTL Cookbook. Lancaster, in turn, borrowed it from a nickname for the Navy Preferred Circuits Handbook, which tech people called “The Cookbook.” But the proliferation of programming cookbooks is almost certainly all SCELBI’s fault.

And to think I never would’ve known about SCELBI — or these early computer game covers — if I hadn’t decided to go outside my comfort zone and dig into early computer history.

If you enjoyed this, please consider supporting the site on Patreon!

Sources

- Dave Tells Ahl: The History Of Creative Computing (Creative Computing – Nov 1984)

- Early Days Of Personal Computers (Creative Computing – Nov 1984)

- Game Playing With Computers (Computers & Automation – Aug 1968)

- Interview with Nat Wadsworth And Robert Findley (Apr 22, 1985)

- Obituary: James S. Mulholland (Jun 13, 2015)

- Oral History Of Kathleen And Dan Spracklen (2005)

- They Create Worlds, Vol. 1 (1971-1982) (2019)

- Van Valkenburg, Nooger & Neville Inc. Against Hayden Publishing Company, Inc. And Hayden Book Company, Inc. (1967)

- The Way Things Were (The Blatant Opportunist – Jul/Aug 2001)

Comments

Join the discussion on my Patreon page!

April 3, 2020

[…] addition to this, I helped Kate Willaert with two articles relating to early video game advertising, I did some work on videos from the Gaming […]

April 11, 2021

[…] being converted from FOCAL to BASIC, it was included in 101 BASIC Computer Games, a DEC collection edited by David H. Ahl. But now it had its Lexington system library name of […]